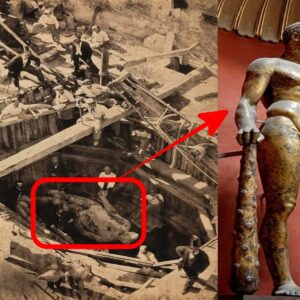

Archaeologists have been excavating ancient thermal baths outside Siena, Italy, since 2019. But just last month, peeking out through the mud and water, small unidentified fragments slowly began to appear: a hand, an elbow, a glimmering coin. Since then, researchers have unearthed 24 perfectly preserved bronze statues dating back some 2,300 years, as well as a cache of thousands of coins and other significant artifacts.

The discovery in San Casciano dei Bagni, a small hilltop town in the Siena province known for its thermal baths, is nothing short of groundbreaking, experts say.

The find is “the largest deposit of bronze statues of the Etruscan and Roman age ever discovered in Italy and one of the most significant in the whole Mediterranean,” says excavation leader Jacopo Tabolli, a historian at the University for Foreigners in Siena, in a statement, per Google Translate.

The statues date back to between the second century B.C.E. and the first century C.E., which was a time of great upheaval in Tuscan history: The transition from Etruscan to Roman rule was taking place, through hard-fought battles over towns such as this one. After the Romans eventually prevailed, they led a concentrated campaign to redefine and minimize Etruscan culture, burying or destroying historical items.

Among the statues are likenesses of Hygieia, Apollo and other Greco-Roman gods. Some of them bore Latin and Etruscan inscriptions with the names of prominent Etruscan families.

“This discovery rewrites the history of ancient art,” Tabolli adds. “Here, Etruscans and Romans prayed together.”

Tabolli thinks that the statues were immersed in thermal waters in a sort of ritual. “You give to the water because you hope that the water gives something back to you,” he tells Reuters’ Alvise Armellini.

Researchers can’t know for certain why the statues were drowned in the thermal waters, but they do know that the waters helped keep them in such good condition. The mud creates an atmosphere without oxygen, which helps keep the bronzes safe from bacteria, says Helga Maiorano, an archaeologist at the University of Pisa, to la Repubblica’s Azzurra Giorgi.

“One of the last ones [of the statues] particularly struck me for the quality of the details,” Chiara Fermo, an archaeologist at the University of Siena, tells La Repubblica, per Google Translate. “It is a female statue, entirely bejeweled, with very detailed necklaces and earrings. An example of what a woman of the time must have been like.”

The area’s thermal baths were used until the fifth century C.E., when public bathing practices were banned under new Christian regulations.

The statues and other discoveries have been taken to a restoration lab in nearby Grosseto. Eventually, they’ll go on display in a new museum opening in San Casciano.